The main challenge was to create a light boat,’ says Ivars Linbergs, a Latvian master boatbuilder and one of three shareholders in Pure Yachts, a new aluminium boatbuilding company based in Kiel, Germany. The other shareholders are Pure Yachts’ founder Matthias Schernikau and performance optimisation specialist Urs Kohler.

Linbergs continues: ‘I had to combine cold, rugged aluminium with refined, crafted foam-cored veneers and end up with a product that is lightweight and beautiful. An aluminium yacht that’s just an aluminium yacht is boring. This boat needs to be everything, a rugged, strong exploration yacht, that’s Matthias’ side, it has to have a warm, welcoming interior, which is my side, and it has to be a high-performing cruising yacht, and Urs takes care of that. Combine the three of us and the result should be an exceptional cruising boat. And indeed, the yard’s motto is “think exceptional”, which also means to always go for the best possible solution.’

‘I don’t like frills,’ says Schernikau with his customary grin. ‘I want to go one step back and build cruising boats made for the sea rather than harbours or moorings. If you want to be alone with the elements on your boat, you need a reliable machine for sailing.

‘Watermakers, pumps, filters, you have to be able to maintain them easily,’ he adds. ‘That’s pure sailing. Ask yourself: do I need this for sailing? If you don’t have an answer in three seconds, you don’t need it. Heated floors, espresso machines, you can have it but you don’t need it - and what you really need must be perfect.

That, in essence, is Pure Yachts. The yard’s first serial yacht, the Pure 42, is a pure sailing machine. Like all the best machines, it’s reliable, robust, well designed, built from quality materials, easy to maintain, and to save weight there’s nothing there that isn’t absolutely necessary. The final criteria of any successful machine is that it performs well, and that is Pure Yachts’ niche in the aluminium market. ‘If you enjoy fast sailing and safe, comfortable cruising, Pure Yachts gives you both,’ says Schernikau.

‘If a client wants a boat to sail through the ice, one that’s safe, stable and strong, well built, but not so much about sailing performance, you don’t need a Pure yacht,’ says Kohler, who spent 25 years at Sirius Yachts, another yacht builder known for its obsession with detail. ‘If you want a boat that does all of that but gives you feedback and is fun to sail, you choose Pure Yachts.’

The Pure 42 features a chined aluminium hull designed by Menzner/ Berckemeyer, hydraulic lifting keel and twin rudders built at the Volmer factory in Holland and trucked to the Pure Yachts yard in Kiel for fitting out. Aluminium was chosen for strength and light weight, because performance is an obsession for Pure Yachts.

‘Performance also gives you safety, not just fun sailing,’ Kohler continues. ‘You can sail away from leeshores in any conditions, you don’t get waves breaking into the cockpit because the yacht can plane down waves. That’s the difference Pure Yachts brings to the whole aluminium cruising yacht market.’

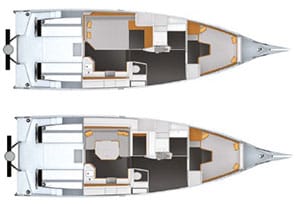

Let’s look at that data. This is a 13.8m yacht that displaces 9.8 tonnes with 3.3 tonnes of lifting bulb keel ballast at 3m draught (1.2m with the keel lifted for taking the ground). The performance package, which this first hull will have, features a Solent-rigged carbon fibre mast by Marechal with a genoa, self-tacking jib and a square-top main adding up to 108m² of upwind sail area (99m² with a pinhead main on an aluminium mast is standard). As well as the performance option, there’s an off-grid package with solar, hydrogeneration and double battery bank, and a liveaboard package with dishwasher and washing machine.

The old shipyard has been extensively upgraded with state-of-the-art facilities. Note the all-glass walls, 5-axis milling machine and frame for visualising interior design configurations. The red floor grid is a hydraulic ‘dry pool’, used instead of scaffolding. | Hull #1 of Pure Yachts’ first production model, the Pure 42, was recently finished. The hulls are fabricated by Volmer in Holland and fitted out in Kiel.

The prototype interior features light oak veneers on laminate-sandwiched 80kg/m³ foam cores of 12, 22 and 42mm with 700kg/m³ foam milled in where fittings attach. Foam can be used because the interior doesn’t need to be structural. ‘It’s strong enough that you could rig and sail it without an interior,’ adds Pure Yachts’ comms man Jan von der Bank. ‘Of course the customer can always choose between a wide range of woods, furniture surfaces and fabrics,’ he says.

The hull and deck are insulated down to the waterline with one layer of 25mm Armaflex, sandwiched in PVC for protection, which is 10 times more effective than rockwool. All seacocks are above the waterline on welded pipes, all tanks vent into the keel box rather than the topsides and all deck fittings are insulated from the hull and accessible from inside the yacht by unscrewing the headlining and pulling out the water-cut Armaflex plugs below each fitting.

The yachts will be delivered fully specified with systems the yard knows work well. Steering is by Jefa, electric winches by Andersen, deck gear by Ronstan, furlers by Facnor, Lofrans windlass, retractable Max Power bow thruster, folding prop, Rocna anchor and Raymarine electronics as standard with NKE in the performance package. It’s ready to sail away.

The 42-foot LOA was chosen as the best size for space on board and ease of handling, says Schernikau. ‘The Pure 42 is our solution for an easy-to-handle, single- or double-handed yacht for owners of any age. Many sailors won’t choose a 50ft yacht because it’s too cumbersome in port, especially in the Baltic where we have small harbours. The twin double-cabin 42 deck saloon gives two people, plus two guests, plenty of space and living comfort to stay on board for a long time, long enough to cruise around the world, through Arctic waters if you want to. For the last 20 years “deck saloon” has meant a motorsailer with a fixed three-blade prop, going at five knots. Our deck saloon concept means fast cruising and comfortable living, even if you’re a little bit older.’

The energy of a start-up is palpable here, and make no mistake, Schernikau is fully committed to this venture. After a childhood spent lake sailing with his family in northern Germany, he developed an impressive record of building businesses. ‘I started my lift company in 1999 when I was 30 years old. I started as a one-man band and I was very busy. I like craftsmanship, I’m a master metal worker. I grew my lift company for 24 years and when I sold it, it had 170 employees. It didn’t feel like mine anymore, it was too big. In 2010 I bought my first aluminium yacht and started sailing again. One highlight was a trip to Iceland and northern latitudes and I loved it so I decided to build my own boat.’

Schernikau approached designer Martin Menzner to develop the idea. ‘At first I was interested in a 45-46ft boat, a normal deck saloon explorer, then I told him about my experience sailing a Seascape 27 – I had a huge smile on my face! He told me a normal deck saloon would not be the right boat for me, so we committed to a 49ft boat – I wanted a little more space. I decided on tiller steering because I don’t like wheels – that’s just me – a lifting keel and water ballast. And my 49ft Gorre goes like a big Laser, it’s amazing to sit on the coaming, tiller extension in hand and looking forward, powering into the wind. You feel the boat like a dinghy.’ And it was always going to be aluminium: ‘I like being at sea with an aluminium boat because it feels completely different. There’s no creaking, no doors jamming at sea. It’s a stiff, strong, lightweight hull.’

‘The first drawings were done in 2016 and I wanted the project complete in three years – that didn’t happen! I had the hull built at Benjamins Shipyard in Emden, Germany, and when the hull was delivered I found room for it at my lift factory, but I was mostly working on my own at the weekends and late evenings. I thought Project Gorre would never be finished but I was given Ivars’ number to help me finish the project and he did.’

Ivars Linbergs was working on the interiors of Elida, a 48ft one-off racing yacht that has a displacement of 7.8 tonnes and sail area of 138m². The hull was built in light Alaskan wood reinforced with carbon fibre, sheathed in mahogany, with a carbon fibre deck. ‘Martin Menzner had a project with the same boatyard, Jan Brugge. He told me about Matthias and his project and that started a conversation that ended with me finishing the project then helping Matthias finish Gorre.’

‘When I began to think about selling my lift company,’ adds Schernikau, ‘ I said “You’re 52, you can sell your company, make a lot of money, you don’t have to work anymore,” but it wasn’t enough. I still think in projects, developing and finishing projects, that’s what I like. One day I was having a break from working on Gorre with Ivars, sitting in the sun with a coffee, and he asked me: “Matthias, what’s your plan after this?” and I thought about building more boats, it’s not my worst idea. That’s the first time I thought about founding a shipyard.’

‘We first met when Matthias came to buy his mast and rigging, I was working at a rigging company,’ explains Kohler. ‘I was a friend of Martin Menzner too, we sail together a lot. He called me to say “You have to come to my office tomorrow evening to meet two other guys, they have a fun idea.” I rang the bell and Matthias opened the door. We both smiled and half an hour later we were talking about founding a shipyard like it was the most normal thing in the world.

‘For eight months we met every two weeks for three or four hours, Matthias, Ivars and me, to work out what we needed to found a shipyard, what the product should be. It works because we’re all different. Ivars brings knowledge of highquality, lightweight interior building, I bring 25 years of technical knowledge and Matthias understands quality modern production techniques. We had the first drawings of the 42, we knew the product would be good, so we started looking for somewhere to build it.’

Through the grapevine Schernikau found out that the former Lindenau Werft, a yard that used to build double-skinned tankers, was for sale. ‘I had to decide to buy or not in two months, but I knew I’d never find another place like this, right on the Kieler Forde. In December 2023 I bought this yard without really knowing what awaited me, and we started planning a shipyard. I have a lot of experience building companies from the ground up, I enjoy it.’

The first thing they did was move Gorre out of Matthias’ old factory and into this yard to finish the last 20 per cent. This was made easier by the fact that the yard has a 60-tonne crane and the roof of one of the build sheds slides open so that assembled sections of tankers could be lifted out and added to the in-build ship on the slip. Gorre was motored up to the quay, lifted into the shed and work began.

Schernikau’s investment has transformed a 20th century industrial space into a 21st century modern production facility. The current build shed has glass walls on two sides, flooding the space with light and giving views onto the Kieler Forde, smooth concrete floors with underfloor heating, sound insulation, bending machines to form aluminium parts, a laser cutter, a 6x4x2m five-axis milling machine and a 53ft dry pool into which in-production boats can be lowered, to make working on them easier. The reason behind this says much about the three shareholders’ shared vision for this yard: happy workers make happy boats for happy clients.

‘It's very important for me to have a good work environment, to have a flat, organic structure,’ explains Schernikau. ‘You always have to be available, it’s very important. You cannot lead a company and do everything yourself, you have to trust people, give them responsibility. You can’t be angry if there’s a mistake, we all make them, but you have to learn. I want employees to earn enough money to live comfortably because a lot of boatbuilders don’t and I can’t understand that. It’s important to explain to clients not just the product, but the philosophy. If they understand both, they understand why we don’t sell boats for €400,000. We didn’t build low budget elevators like the big manufacturers, we built special projects. Our 42 is also a special project, it’s not something the mainstream manufacturers would make.’

The Pure 42 is designed to combine the liveaboard practicality of a deck saloon yacht with the speed, responsiveness and fun of a performance cruiser. | The standard layout has a midships double cabin beneath the deckhouse. The performance option has 108m² of upwiind sail area on a carbon rig. | The lifting keel has 3.3T of ballast on a 3m fin and retracts to 1.2m draught. The boat can dry out on its keel and twin rudders.

‘If you have a job, it’s not only money, Kohler adds. ‘It’s important to feel good about what you do, to feel appreciated. That’s why we have the glass walls, to give the best possible workspace. Another thing is tools. Many companies buy 10 screwdrivers for 21 workers. Here we give every person their own tools and machines, everything they need to do their job. They take care of them, they don’t lose them, the settings are always right for them. That’s why they give so much back, they feel appreciated. That’s a big theme at this company.

‘We don’t just give them a job, we give them a project. “Today you are building a bathroom.” So they’re not just responsible for the woodwork, but for the floor, the shower cabin, the whole thing. The boss isn’t responsible, the worker is responsible. They work in a completely different way. They bring all their knowledge and experience to the job. If they hit a problem or need help, they can ask and someone else will say “I’ve got an idea, I can help you.” A lot of good ideas come from the workshop, not from the office. They’ll ask if this idea is OK and we’ll say “Yes, it’s a good idea. Let’s do it,” Or “Let’s work with the construction office to see if we can make it even better.” It’s a good way to work.’

The yard also has a generosity of spirit and a willingness to invest in the next generation. Kiel Polytechnic gave its naval architecture students the task of designing and building humanpowered vessels that would be tested on the water right next to the yard. Some prototypes needed running repairs and they approached Pure Yachts who were happy to help and took no payment for their time and materials. Kohler takes up the story.

‘Two weeks later they came back with a crate of beer to say thank you. One of them said: “I’m a master boatbuilder studying to be an engineer but I need to do 40 days’ work experience at a company while I study. Can I do it here?” We said “Yes, no problem. Once a week, if you have time, you can work here.” He came and was a really good technician. Then another came, also working one day a week and more during holidays. He’s doing a masters and asked “can I write my master’s exam about this company?” We said yes, then the professors came to check us out and we’re getting more and more involved with these guys. The third is a female student, I hope she stays too. It brings a lot of young people to us and the appreciation we give to the workers, the sense of team membership, gives people a confidence that they carry back to their studies. When we had some questions about welding and hydrodynamics, we took it to our interns, asked if they could get advice from their professors, and we got a good answer. We’re helping them, they’re helping us. It’s a good investment in the future to get these guys in.

‘Shipyards are changing all the time. With so many high-tech machines you need fewer workers but more people in the construction office, programming the machines. It used to be 90 per cent of staff in the workshop and 10 per cent in the construction office, today it’s more like 60:40 and they’re helping us on the construction side. They also get the practical workshop knowledge, which is important.’ While embracing technology, there is also a determination to leave no stone unturned in delivering the perfect machine for sailing. This included making a plywood mock-up of the interior inside a steel frame made using the laser-cutting files creating an accurate replica of the space between the two watertight bulkheads.

‘It gives us the confidence that everything works, and we have made changes because of this,’ says Kohler. ‘If you only look at a 3D model, zoom in, zoom out, you never get a real feeling for how much space there actually is. You have all these measurements, but does it work? This was just for us and for our clients to get a feeling of the space. If we build it 100 per cent right the first time, we can just press a button for the next boat – but you have to be sure it’s correct first.’

Despite the pressure of deadlines, Schernikau had no doubt it was the right thing to do – indeed it was his idea to build the mock-up: ‘Sometimes we think we must move quicker but it’s the first one, it has to be right.’

That is the hope Schernikau and his staff all share for the Pure 42, that it hits those sweet spots: that it rekindles the excitement of sailing while indulging the urge to explore. ‘A lot of our clients have finished working, their children have gone and they want to live their dream while they’re still young enough to do it. That’s my situation – except most people decide to buy a boat, not found a shipyard.’